Do Online Five-Star Ratings Hold Any Real Meaning?

How frequently does a business you patronize indicate that you might not be their ideal customer? Does your neighborhood café ever suggest you should be tidier while enjoying your pastry? Have you ever been advised by a clothing store to spend less time trying on outfits?

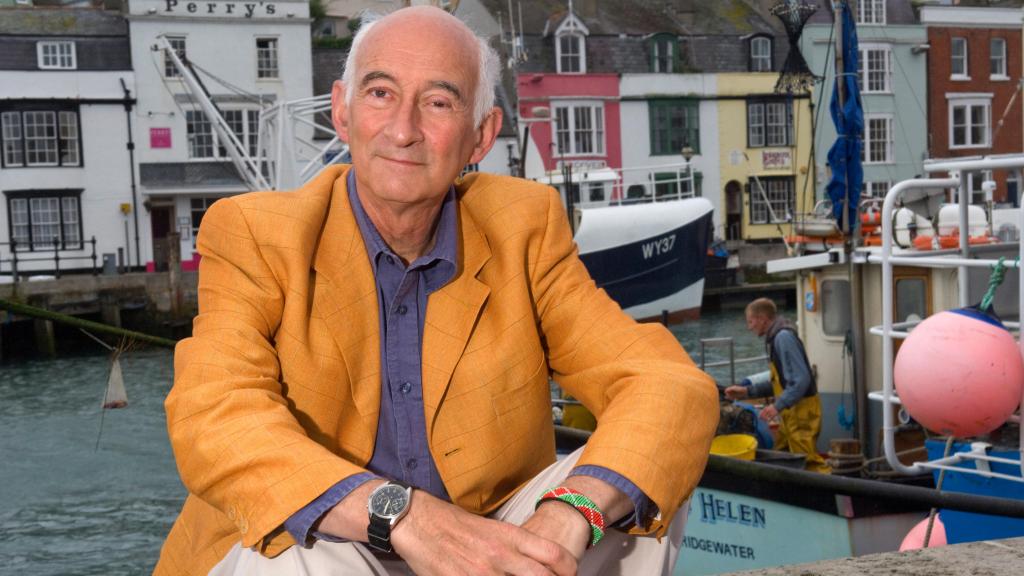

Recently, an email from Uber caught my attention with its subject line: “We’ve noticed your rating could use some help.” The message maintained a subtly passive-aggressive tone: “Harry, the Uber rating system is designed to facilitate a two-way feedback mechanism that fosters a respectful and safe environment for both riders and drivers.”

Upon checking my customer rating — yes, everyone has one — I found it was 4.57 out of 5. I considered this a reasonable score, yet it appeared insufficient enough for me to be reminded that “a courteous and positive approach significantly contributes to the overall experience” and that I should “keep interactions with drivers light and friendly.”

While in the USA, I casually inquired with my next driver about any possible infractions on my part. Upon learning my rating, she responded with shock: “Oh my God, that’s awful! Had I seen that score ahead of time, I wouldn’t have accepted this ride.” Her genuine concern suggested she feared she had picked up an unruly passenger. “That implies you are not a great passenger,” she remarked.

Am I impolite? I do not believe so. Have I called my driver to inquire about their delay after being told they’d arrive in four minutes only to wait thirteen? Yes, that has happened.

My real issue lies not with my comparatively low rating but with the requirement to be rated at all. We now exist in a feedback-centric economy where each interaction must be reviewed and recorded, no matter how trivial.

My inbox inundates me with requests for evaluations. “How was your experience?” asks the local bakery. Trainline requests, “Could you spare two minutes to provide feedback on your recent booking to Watford Junction?” Most astonishingly, after a visit to the emergency department for a wrist injury, I received a text asking, “How likely are you to recommend our emergency services to others?” An enjoyable outing, superb X-rays, definitely a recommendation!

The root of this trend can be traced back to eBay. In 1997, during the early days of the internet, the auction platform launched its Feedback Forum, wherein buyers could rate sellers as “positive”, “negative”, or “neutral” along with comments. Jim Griffith, the first customer service representative for the company, believed it was critical to the success of eBay and online commerce as a whole. “As trusting as consumers may be, they require that extra validation,” he noted in a discussion.

In a marketplace filled with sellers going by usernames like JSmith5678 instead of recognizable brands, reassurance of reliability proves beneficial. I completely understand that. Consumer feedback can be incredibly useful: a particular shirt might run larger than anticipated, or a flat-pack table proves challenging to assemble.

However, the rating system is fundamentally binary. A score of 1 point is awarded for “positive” and a deduction of 1 for “negative”. For many eBay sellers, anything less than a 98 percent rating was devastating. Numerous businesses have faced peril from feedback manipulation, especially restaurants on Tripadvisor, where patrons have demanded complimentary meals in exchange for favorable reviews.

Just this week, I purchased a jacket through the second-hand clothing platform Vinted. It was affordably priced, arrived promptly, and matched its description, yet it had a noticeable cigarette odor. Under a practical feedback system, I would have considered leaving three stars, but I realized that could harm their business, so I opted for five stars and sent them a private message instead.

This discrepancy occurs because under the five-star rating framework — employed by platforms like Uber, Tripadvisor, Airbnb, and Vinted — five stars has morphed into a catch-all for everything from “exceptional” to “tolerable, I guess.” In contrast, a single star signifies a truly poor experience. Statistically, this phenomenon is known as the J-curve. A 2021 study published in Nature revealed that over 80 percent of online reviews receive four or five-star ratings, resulting in a “positivity problem” that makes discerning among products and services nearly impossible.

The typical Uber passenger rating in the UK sits at 4.83, while in the USA, it’s 4.9, which clarifies why my 4.57 is seen as abysmal.

A few years back, the Harvard Business Review investigated the distortion of ratings and proposed a solution: a weighting system that would give more importance to those reviews that showed discernment. Someone providing a varied range of ratings could have their reviews prioritized over someone who always rates five stars or frequently gives one star. This adjustment might mitigate the J-curve effect but not our fixation on obtaining feedback.

This obsession has crept into professional environments, where Generation Z employees, according to employers, request not only frequent updates on their performance but also that these assessments be consistently positive. Perhaps if you’ve grown up in an era where a product receives an average of 4.8 stars from 13,000 Amazon customers, anything less than a remark of “you’re excelling” feels like a significant setback.

Let’s allow buyers or Uber drivers to provide commentary; perhaps we should even reward constructive feedback. AI is becoming adept at discerning tone in written communication. However, we should eliminate all forms of rating or star systems. The economic principle known as Goodhart’s law states that when a measure becomes a target, it loses its value as a measure. As such, five-star evaluations have transformed into a mere placeholder and now offer no real significance.

Nonetheless, please feel free to leave a five-star review for this column in the comments below.

Post Comment